Esek Hopkins House

A three-hundred year old house with a varied history, a little mystery, and larger questions about what is worth preserving.

images of this Property

-

1932. Rhode Island Photographs Collection, Providence Public Library -

1950. Rhode Island Postcard Collection, Providence Public Library -

Photo from the National Register nomination form, 1973, photographer uncredited -

Photo from the National Register nomination form, 1973, photographer uncredited -

![]()

Three quarter view of the adjoined structures, looking northeast -

![]()

View north what is known as the Gable Portion, a two-story hall with a front hall and main stair, built circa 1760. -

![]()

Plaque on the south-western face of the Gable Portion, reading “Esek Hopkins; 1718 – 1802; First Commander-in-Chief of the American Navy Lived in this House” -

![]()

An entrance door on the circa 1760 Gable Portion, likely added and revised in 1840 to reflect the Greek-revival style. The “1756” number reflects not the address, but the year the house was purchased by Esek Hopkins. -

![]()

The southern face of the Gambrel Portion, likely built before 1756. -

![]()

A three-quarter view of the two oldest structures, looking northwest. -

![]()

Looking west at the eastern face of the Gambrel Portion. -

![]()

The rear of the Gambrel and Gable portion as well as the ell, looking southwest. -

![]()

The eastern face of the ell addition, looking west. -

![]()

Another three quater view of the ell portion, looking aouthwest and showing the end of the well house. -

![]()

A pulled back view of the entire northern and eastern faces, looking south. -

![]()

Detail of the well house outbuilding at the end of the ell addition, looking south-southeast. -

![]()

Interior detail of a wall in the Gabel Portion structure, showing wide wood planks under a layer of plaster. Behind these vertical planks are diagonal cross-planks which are then covered in exterior clapboards. There is no room for insulation in these walls. -

![]()

A pulled back view of a similar scene on the same wall, looking southwest. -

![]()

Wall construction detail from the Gambrel portion of the house. -

![]()

Wall construction detail from the Gambrel portion of the house in what had once been a kitchen -

![]()

Door latch detail. -

![]()

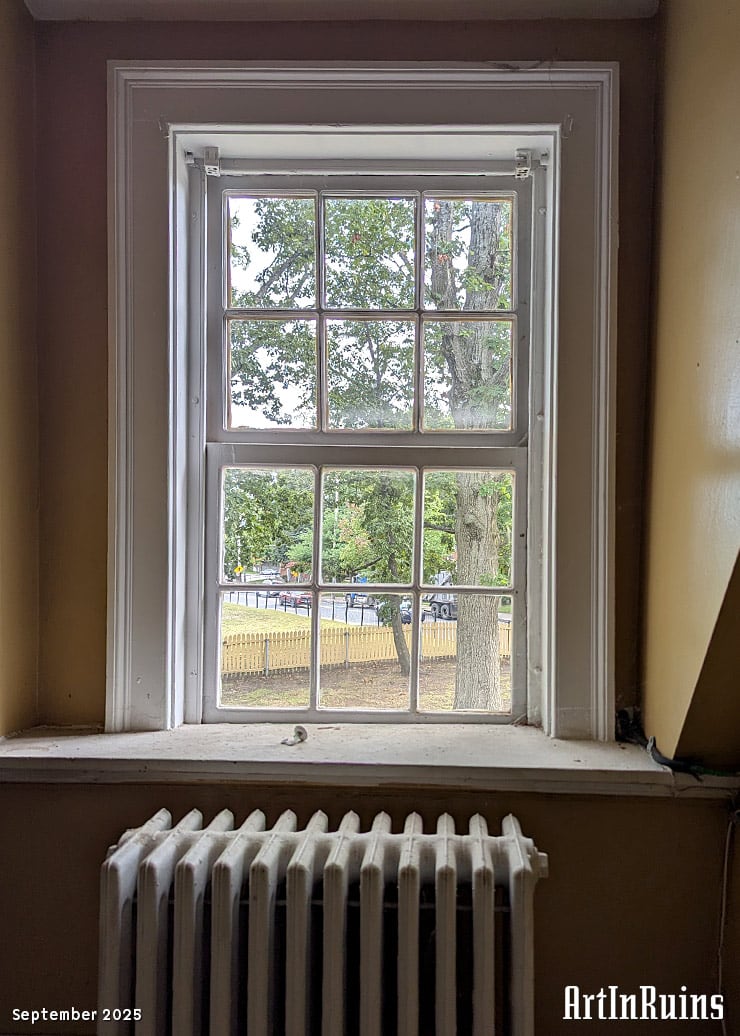

Interior window and shutter detail. Windows are 12 over 12 lites in a double-hung configuration. Notice the heat registers added below windows to heat the air in front of drafty single-panes. -

![]()

The large three-foot-wide hearth with “Beehive” over in the 1820–1840 ell addition. The baker would have scooped coals from the main fire into the adjacent oven and closed the door. Once the oven was at the right temperature, they would then scrape the coals onto the floor and place whatever dish they were preparing inside the oven. -

![]()

Wall plaster detail with un-original chair rails added a later time -

![]()

The wheel above the water well in the well house. -

![]()

Detail of a doorway leading into a tool shed and a western entrance. -

![]()

What is likely the oldest stairway in the Gambrel Portion of the structure. -

![]()

Peeling paint and a later-added electric light as one ascends the stair. -

![]()

A room in the Gambrel Portion with plaster removed exposing the underside of the roof. -

![]()

A hearth on the second floor of the Gambrel Portion. -

![]()

Window dormer detail on the second floor of the Gambrel Portion.

31 images: Press to view larger or scroll sideways to see more. Contributions from the Providence Public Library Digital Collections

About this Property

About Esek Hopkins and the Homestead

Whenever we start talking about a person who was born more than 300 years ago, we know their history and how they made their living will be controversial. Esek Hopkins was no exception.

Esek’s brother Stephen Hopkins became governor of Rhode Island in 1755 and would serve as the 28th, 30th, 32nd, and 34th governor. He was a signer of both the Continental Association and Declaration of Independence as well as the 3rd, 5th, and 17th Chief Justice of the Rhode Island Supreme Court.

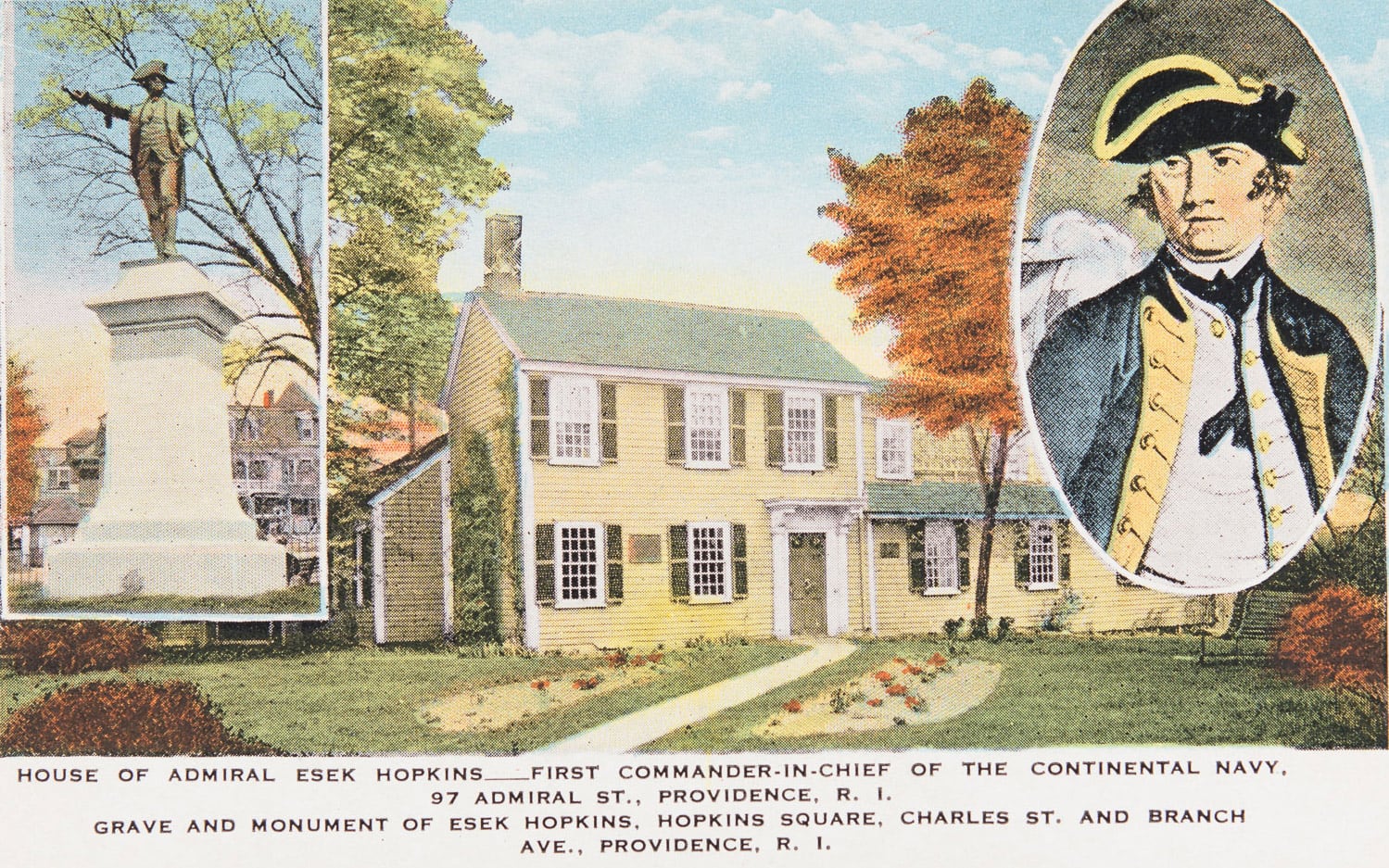

Esek’s accomplishments include persuading the British not to occupy Newport in 1774; being the first Commander-in-Chief of the newly formed Navy during the American Revolution (and the only Commander-in-Chief during the American Revolution) from October 1775 to January 1778; leading The Raid of Nassau, an assault on a British colony on March 3, 1776, the first U.S. amphibious landing, which successfully captured munitions desperately needed for the War; and he is credited with establishing the Marine Corps. Admiral Street is in fact named for Hopkins, its most famous resident.

While those accomplishments are strategic and important, Hopkins’ history with the trade of enslaved people puts them in a different light. In September 1764, during his time as a privateer and merchant, Hopkins took command of a slave ship named Sally, owned by Nicholas Brown and Company. Hopkins had no prior experience in operating a slave-trading vessel, and the 15-month voyage would result in the death of 109 out of 196 people. The disaster was said to have helped turn Moses Brown against the Atlantic slave trade in stark contrast to his brothers. He was 46 at the time of this voyage with 20 years of experience at sea. This tragic loss of life shows how brash the commander was, and makes his military victories seem like pure luck or obliviousness to the consequences of his actions and commands.

The house, which underwent many architectural changes, also underwent changes in residents and their staff, which included enslaved people. Hopkins lived briefly at the house with wife Desire Burroughs and their nine children. After Hopkins died in 1802, his daughters inherited the property. It remained in the family for the next century until 1907, when the last living descendant, Elizabeth West Gould, passed. The house was then donated to the City of Providence.

In 2021, an artist residency pilot program launched in the house and the Haus of Glitter was its first participant. They collectively wrote and performed a Dance Opera and historical intervention called “The Historical Fantasy of Esek Hopkins” to directly address the racist legacies that are part of historic preservation.

Architecture

The building is thought to have been constructed over four different periods — each involving the potential of existing structures.

- circa 1730–1740

- Before the acquisition by Esek Hopkins, it is thought that the eastern wing and gambrel-roof portion of the structure already existed. It is certainly a stand-alone dwelling, with two rooms and a kitchen on the first floor, a curving staircase, and bedrooms plus a hearth on the second floor.

- circa 1760

- Esek Hopkins purchased the land and the buildings thereupon in 1756. Shortly after he supervises the construction of the Gable Portion, a western two-story addition to the Gambrel Portion, with western fireplace and a new front entranceway with stair behind. Windows and fenestration were likely the same 12 over 12 lites and simple stick frame style as we see today.

- circa 1800

- The First Ell Addition was added and likely used as a kitchen before the ell was later added onto. It was laster used as the Dining Room.

- circa 1820–1840

- It is thought that an existing building was moved and added onto the northern face of the newest ell addition. This section included a new kitchen with a Beehive stove as part of the large fireplace and a storage and tool room. The water well was enclosed in its own well house by 1840.

- circa 1840

- The entire ell was updated with trim and details to reflect the Greek-revival style.

- 1865

- The entire home is said to have been “Victorianized,” which means it had been renovated or altered to incorporate elements of Victorian architectural style. It may also have included indoor plumbing, as that started to become widely available by 1850. Windows were changed to modern 2 over 2 panes.

- 1906–1908

- Esek Hopkins’ last remaining prepared the house to be handed over to the City as a historical property by restoring the house to as much of the original as was possible. This means any architectural flourishes that were deemed too “Victorian” were likely removed. The windows were changed back to the 12 over 12 style. The building was donated to the City of Providence in 1908 with the stipulation that it be “used for patriotic purposes, and kept as a park.”

- 1958

- The City went about an extensive remodel of the building to make it habitable as meeting and office space. Heating and plumbing were renovated and added along with wiring and some exterior work. The rear of the house was remodeled for modern bath and kitchen facilities while the second story was made into a caretaker’s apartment.

- The Daughters of the American Revolution used the house for many years as their main meeting place and office.

- 1973

- Additional slight remodeling was undertaken.

If the house is worth saving — complete with its complex and painful legacy — than what kind of preservation is appropriate? In order for the house to be livable, its basic construction can not support today’s standards of efficiency. The walls are thin and further modification of the interior would significantly change the structure. At the same time, so much has already been changed in the home, is there anything truly “original” left to preserve?

For us, it would be interested to enclose the house in a greenhouse structure. Put all of the HVAC and insulation into a new surrounding structure that can envelope the home and keep it intact as it stands now. Keep some walls exposed as an exhibit of building methods and how they have changed over time. Excavate sections to more fully understand how the house changed over time and why. As a cross-section of three centuries of architectural advancement, it might be the most interesting.

Current Events

The house is owned by the City of Providence and under the management of the Parks Service. Occasionally groups will use the house — most recently, the Providence Preservation Society has been holding historic restoration classes there A permanent program for the house and its preservation is sought by the City.

Further Reading

- Dave Bowman Does History: Esek Hopkins

- Rhode Island’s Esek Hopkins – Rodney Dangerfield of the American Revolution, New England Historical Society

- Dispatch from the Esek Hopkins House: Historic Hearths, Providence Preservation Society

In the News

What and Why RI: Hopkins Homestead: From Revolution to reinvention

by Katie Landeck

Providence Journal | October 22, 2023 (abridged)

The homestead, which has grown with additions, has had a few lives since its donation to the city.

At the end of Admiral Street in Providence, next to some soccer fields and just up the street from a Dunkin’, is a little yellow house that is clearly from another era.

The 21/2-story gable house, with its surrounding maples and picket fence, has clearly resisted change (albeit not entirely; there’s an addition and a paved driveway) while the area around it has not.

It’s the type of curiosity that drew the attention of a What and Why RI reader who wrote to ask what we could find out about the house.

Who was Esek Hopkins?

The house at 97 Admiral St. was built by hand in 1756 for none other than the first commander of the U.S. Navy, Esek Hopkins.

When he built the house, though, the American Revolution was still a ways off.

Hopkins was born on April 26, 1718, to a well-to-do family in Scituate. But at 20, he rather brashly set out for a life at sea on a ship bound for Suriname in South America. Two of his brothers set off with him on that first trip into sugar and slave trading, and both of them died onboard, but Hopkins decided this was the life for him.

He married in 1741, and 10 years later, he moved his family from Newport to the 200-acre farm that the Esek Hopkins Homestead was once the heart of, according to the documentation when the house was submitted for the National Register of Historic Places. But the farm was largely unsuitable for farming, and Hopkins preferred the sea anyway.

In the Seven Years’ War, Hopkins, known for having a rather aggressive nature, had a knack for plundering French vessels and thrived as a privateer, according to the New England Historical Society.

When the war ended and privateering stopped, Hopkins was commissioned by the Brown family to sail a slave ship, the Sally, to North Africa, as a component of plans to turn Providence into the political and commercial center of Rhode Island, over Newport. The voyage was a disaster. He bought 167 humans to sell as slaves, and by the time he returned to Rhode Island, 109 Africans had died.

When the American Revolutionary War broke out, Hopkins was tapped to defend the Colonies. He famously persuaded the British to not occupy Newport in 1774, and in 1775 was appointed commander in chief of the Continental Navy’s fleet and given a fleet of eight merchant ships that had been converted. The following year, he made an attack on a British colony in Nassau, where he captured two ships but failed to capture the third, the Glasgow. Because he didn’t capture the Glasgow and for disobeying orders, he was censured by Congress and ultimately dismissed from the Navy.

He served in the Rhode Island General Assembly through 1786 and died on his farm in 1802.

Just over 100 years later, the homestead, which had been passed down from family member to family member, was donated to the City of Providence in 1908, with the stipulation that it be used as a public park. At the point it was given to the city, it had already been listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

What happened with the Esek Hopkins Homestead after it was given to Providence?

The homestead, which has grown with additions, has had a few lives since its donation to the city. For a time it was a museum, then it was rented out, and then it was used for Providence’s “Park-ists” in Residence program.

From December 2019 to November 2022, the Haus of Glitter moved in after their artistic director, Matt Garza, secured the residencies. A dance company, performance lab and preservation society that centers on the experiences of queer people and people of color, Haus of Glitter asked questions about what it means to inhabit a space imbued with the history of the white supremacist slave trade.

“During this time, we worked to heal + transform the space to create work that investigates lineage; and restores the energetic center of its layered history towards Queer/Feminist BIPoC Wisdom, Healing, & Liberation. Everything we have created + will create here is a protest-demonstration against the system that tells us that Esek Hopkins’ home, a symbol of his legacy of white supremacy, is worth preserving,” Haus of Glitter wrote on their website about their time in the house (emphasis theirs).

At the end of the grant, they created “The Historical Fantasy of Esek Hopkins,” a dance opera that reimagined the story.

With the residency over, the house is about to move into its next chapter. The city has partnered with the Providence Preservation Society to turn the house into a learning laboratory for its Building Works program.

The preservation society has long been familiar with the Esek Hopkins Homestead, listing it as one of the city’s Most Endangered Properties in 1995 and collaborating with the Haus of Glitter during its residency.

Considering how much work the building needs done, the house was a natural fit for the Building Works program, said Kelsey Mullen, the preservation society’s director of education.

“We do a lot of training around workforce development in the preservation trades and also teaching people, just regular residents, how to be a little bit handier and more capable when it comes to caring for older properties,” she said. “The idea of a project house kept coming up, having a building with some practical challenges that we could show people in real time.”

The house needs a lot of work, so the relationship is “indefinite,” Mullen said.

“We will continue to use the site for training and fix it up and maintain it as long as we can,” she said.